Berenice Abbott & Raphaël Dallaporta

Since its beginnings in 1839, photography has been a rich, potential source of inspiration for scientists. We can see what’s invisible – from the infinitely teeny to the infinitely huge –because of it, at the beginning of the 20th century, the avant-garde grabbed this scientific iconography, reworked it and adapted it to their own artistic needs. Photography’s keen appeal is as strong as ever and continues to gain momentum.

We have never held a show in the gallery with scientific overtones, so we are more than pleased to exhibit the photography of both Berenice Abbott and Raphaël Dallaporta. Although both working in different areas – fundamental physical mechanisms for one and anatomical parts for the other – the rigorous composition of each image puts both photographers on the same creative line of expression. Beyond their obvious visual force and affect, both bodies of work explore in a forthright manner a new universe, devoid of anecdotes and aestheticism. Thanks to their varying levels of interpretation, these photographs require us to ask questions about our own understanding of the world around us.

-

Berenice Abbott, Soap Bubbles, New York, 1946

Berenice Abbott, Soap Bubbles, New York, 1946 -

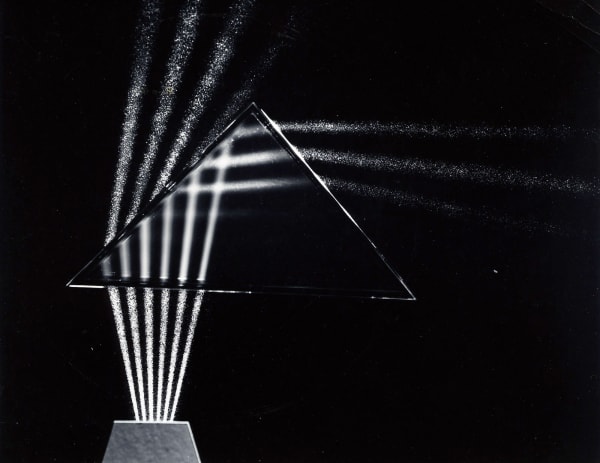

Berenice Abbott, Light through prism, Cambridge, Massachussetts, 1958-61

Berenice Abbott, Light through prism, Cambridge, Massachussetts, 1958-61 -

Berenice AbbottCycloid, Cambridge, MassachusettsTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur12,4 x 49,5 cm

Berenice AbbottCycloid, Cambridge, MassachusettsTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur12,4 x 49,5 cm

Dim. papier: 33,3 x 61,8 -

Berenice Abbott, Stroboscopic Angle shot, c. 1958

Berenice Abbott, Stroboscopic Angle shot, c. 1958

-

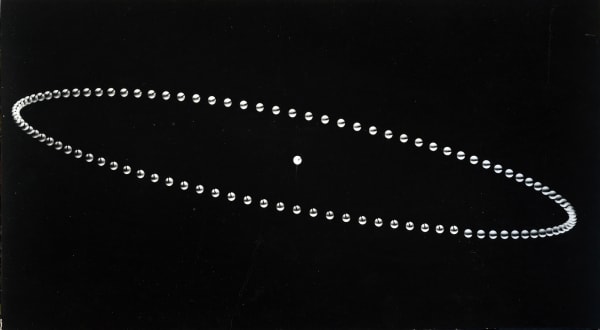

Berenice AbbottMultiple Exposure of a Swinging BallTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur32,5 x 49,5 cm

Berenice AbbottMultiple Exposure of a Swinging BallTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur32,5 x 49,5 cm

Dim. papier: 60,9 x 76,2 cm -

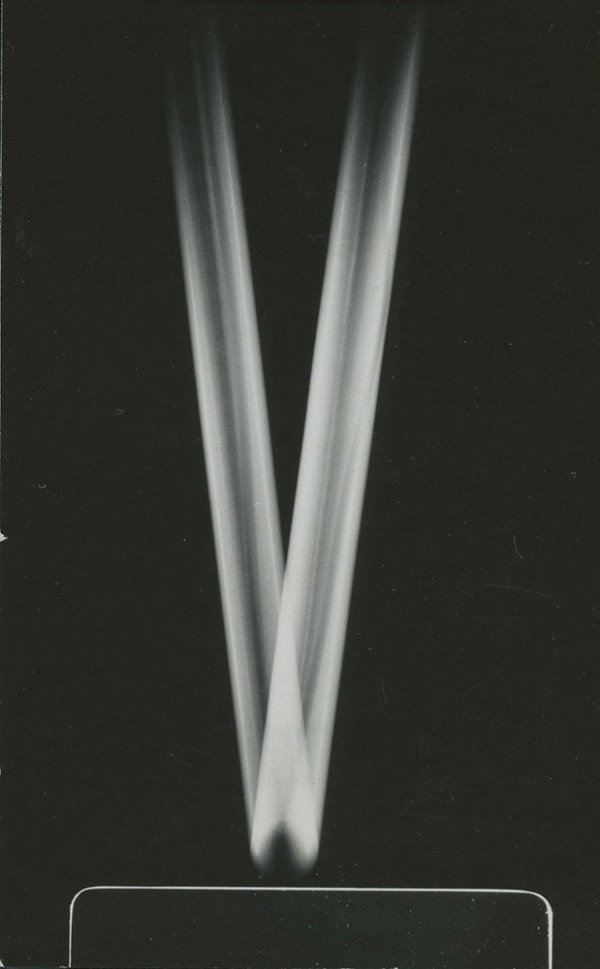

Berenice AbbottTransformation of Energy, Cambridge, MassachusettsTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur26,4 x 34 cm

Berenice AbbottTransformation of Energy, Cambridge, MassachusettsTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur26,4 x 34 cm

Dim. papier: 40 x 50 cm -

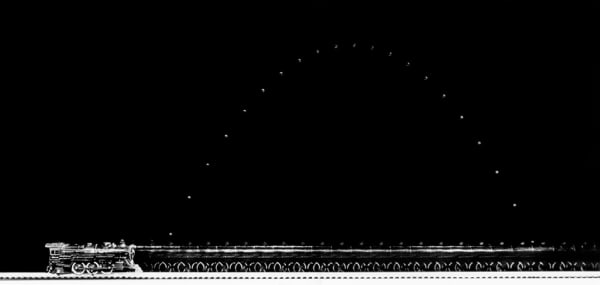

Berenice AbbottMultiple exposure showing the path of a steel ball ejected vertically from a moving object, Cambridge, MassachussetsTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur22,9 x 33 cm

Berenice AbbottMultiple exposure showing the path of a steel ball ejected vertically from a moving object, Cambridge, MassachussetsTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur22,9 x 33 cm -

Berenice AbbottTime Exposure Angle ShotTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur24 x 34 cm

Berenice AbbottTime Exposure Angle ShotTirage gélatino-argentique postérieur24 x 34 cm

Dim. papier: 40 x 50 cm

Berenice Abbott, Documenting Science

« We live in a world made by science. But we – the millions of laymen - do not understand or appreciate the knowledge which thus controls daily life. »

Letter from Berenice Abbott to Charles C. Adams, New York City, April 24, 1939.

In 1939 Berenice Abbott started to want to make photographs of scientific phenomena. She experimented making photographs of magnetic fields, soap bubbles, and wave patterns. All of these photographs illustrate the reality and order of their subject consistent with the artist’s vision.

Abbott had no formal training in any scientific discipline, but she was endowed with an inquiring mind, a prophetic sense and the perseverance with which to push into the largely unexplored field of scientific photography. She bought secondhand texts on physics and electricity and though she lacked the background to understand them fully she saw how poor most scientific photographs were.

Abbott’s ideas about science and photography sounded good ; they looked good on paper but they met with no response. On October 4, 1957, an event occured that to Abbott’s mind saved her life : she saw a newspaper headline announcing the sucessful launching of Sputnik on that day by the USSR. According to the article that followed, the Societ success indicated that the United States was falling behind in science, and she remembers thinking, « I wonder if anyone would be interested in scientific photographs now ? » She did not have to wonder very long.

In February, 1958, she talked with Dr. E. P. Little of the Physical Science Study Committee directly. Her passion to convey the world of science through her art was resolute and culminated in her work for this group at MIT in 1958. PSSC was created to reformulate the way science was taught in American high schools. Abbott’s photographic illustrations fundamentally changed the way thousands of students visualized some of the principles of physics.

In this day of digital cameras and computer-generated imagery, it is difficult to realize the enormity of her work. First, she had to learn and understand the fundamental idea that needed illustration. Then she needed to envision the photograph required to capture that concept, devise the equipment and lighting to make the photograph, load and unload sheet film in a bulky view camera, develop the negative, and finally make a print that was as true to the science as it was to her aestheticism.

These images are timeless in the elegance of their simplicity and the clarity of her vision. Many seem to be abstractions, but they are not. Each one teaches and illuminates. They are still true to that ideal today, fifty years later.

By 1961, « The Image of Physics », a touring exhibition by the Smithsonian Institution Exhibition Service (SITES) effectively achieved the photographer’s goal of bringing scientific explanation to a mass audience, offering many Americans their first experience of viewing original fine art photography.

Into the 1980s, the PSSC curriculum’s practical labs and memorable photographs conveyed modern physics and principles of science methodology indelibly to a generation and more of American high school students – fulfilling Abbott’s quest to « understand or appreciate the knowledge which thus controls daily life ».