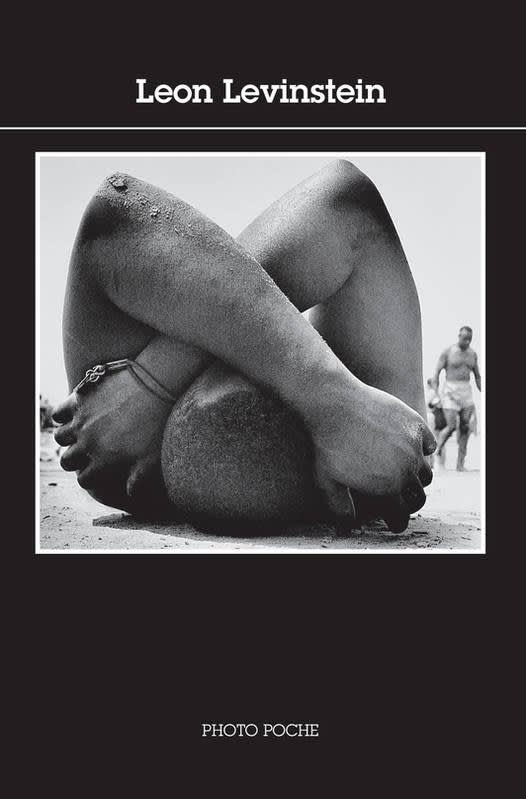

Leon Levinstein: Choreography of the bodies

Les Douches la Galerie is pleased to present its first solo exhibition dedicated to the work of Leon Levinstein. Composed of some thirty photographs taken over nearly thirty years, from the 1950s to the 1980s, the exhibition is a walk through the city, up close to the bodies that deploy themselves there. It was conceived in partnership with the Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York.

Opening on January 26, 2023 from 6 to 9 pm

-

Leon Levinstein : un autre regard sur la Street Photography new-yorkaise

Eléonore Bully-Garilli, Phototrend, 16 March 2023 -

Double exposition Leon Levinstein et Robert Frank aux Douches

Carine Dolek, Réponses Photo, 7 March 2023 -

Sélection galeries : Robert Frank et Leon Levinstein aux Douches

Claire Guillot, Le Monde, 4 March 2023 -

Leon Levinstein : New York par le prisme du corps

Costanza Spina, Fisheye Magazine, 1 March 2023 -

Leon Levinstein et le corps des autres

Frédérique Chapuis, Télérama Sortir, 1 March 2023 -

Leon Levinstein - La chorégraphie des corps

Frédérique Chapuis, Télérama Sortir, 31 January 2023

THE WEIGHT OF HUMANITY

In the 1960s, if you were hanging around Times Square or in the working-class neighbourhoods of the Lower East Side, Coney Island or Harlem, it was not uncommon to see a tall, lanky silhouette – very boney and hardly appealing – belonging to the son of Lithuanian immigrants. As a member of the only Jewish family in their tiny village in West Virginia, Leon Levinstein worked as a graphic designer in New York, at the obscure Colby Advertising Agency.

Like Vivian Maier, Levinstein (1910-1988) spent his life photographing the streets. Like her, he kept away from the worlds of art, photography, galleries and museums. He did not dream of making a book; he did not get commissioned work; he did not benefit from having his photos appear in magazines; he did not receive the recognition he deserved and that he did not seek. Rather, he believed that his passion for photography was part of his private life.

Unlike Maier, however, he installed an enlarger and tubs with developing fluid in his dilapidated flat under a pipe, like a semblance of a dark room. He developed his own prints. Towards the end of his life, he even discovered that his photographs were so well-appreciated that Edward Steichen, the director of the photographic department of the Museum of Modern Art, had collected them and had included some images in a historical milestone – a collective exhibition from 1955 of 273 artists entitled “Family of Man”. His work was almost exhibited in Ken Leyman’s gallery Photograph. And he even won a Guggenheim Fellowship!

Which is not really surprising: after enlisting as a propeller repairman in the Air Force in 1942, he subsequently opted to take classes with the Photo League, and as part of that institution, also with Sid Grossman, a charismatic, dedicated professor who had a reputation for creating an atmosphere of introspection and group psychotherapy. He also attended the design workshop of Alexey Brodovitch, the artistic director for Harper’s Bazaar.

The Great Depression of 1929 had terrible after-effects. It was the subject of investigations, in rural areas, by the formidable reporters of the Farm Security Administration, including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and Gordon Parks. Through the snapshots made possible by the invention of 35mm, documentary photographers gained an added social value. Their commitment to political and economic life was crucial. Their advocacy sometimes resulted in laws being changed.

Although he mingled with the progressive Jewish bohemian clique, Levinstein was not spurred by that ambition. He was what Walter Benjamin called ‘un flâneur’. He found inspiration and excitement among the crowds in the public spaces of working-class neighbourhoods. He was a tall, solitary heavy smoker who appears never to have been in a romantic relationship; he seemed to drag along rather than walk, brushing close to walls, always on the margins, contemplating rather than participating in life.

He managed the amazing feat of sneaking into crowds and seeming invisible; no consent or participation in the shot was necessary. Before using a Leica, he turned his twin-lens reflex camera – which dated from the war – on its side such that the people being photographed were entirely unaware of what he was doing.

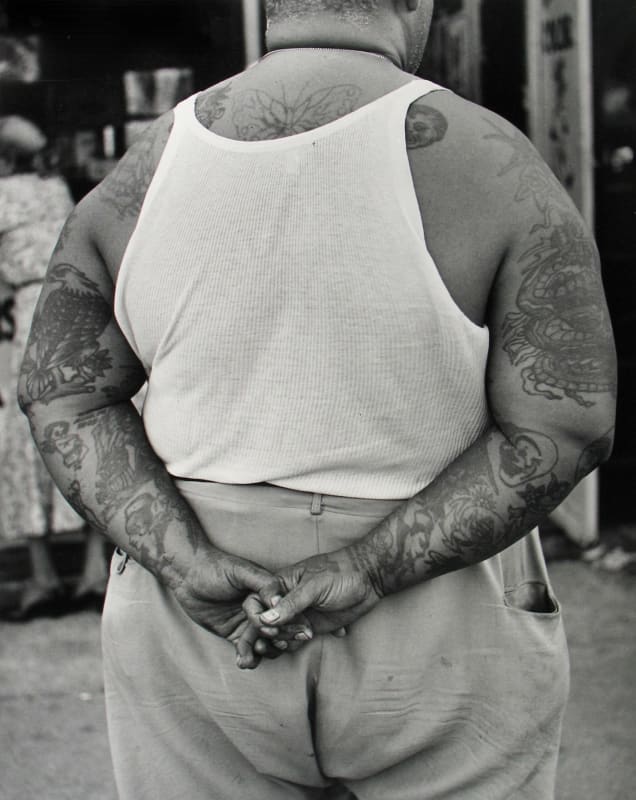

Robert Capa (1913-1954) would not have had to tell this inventor of Street Photography to ‘move closer!’. Levinstein really went up close. Tramps, bathers, prostitutes, rabbis, lovers, elderly folk and children filled the void of his life. He renders these people at nearly life size, captured up close, in great detail. He makes them seem almost tactile, with a powerful density of body accentuated by the fact that he fills the image from edge to edge by framing them in an incredibly brutal manner.

Like Lisette Model (1901-1983), he uses the body’s heaviness amplified through the brutality of close-ups. His particular thing was the weight of bodies, but also, and equally, the weight of humanity. Nevertheless, he sometimes allowed himself to focus grotesquely on some worn-down middle-class woman he met, who had become a caricature of herself. In those moments, the surrealistic strangeness of exaggerated faces comes through in the close-ups.

As with William Klein (1926-2022)’s photographs, the foregrounds literally stick to the lens, revealing the film’s grain and a violent contrast of light. As such, we feel surrounded by their presence, we feel that shiver of being slightly suffocated at the centre of a crowd.

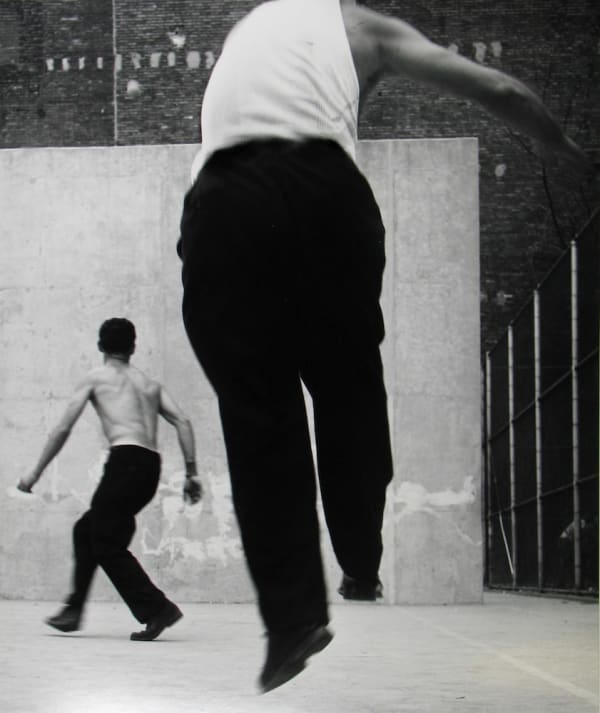

A very strong sense of tension – the vital energy and febrile modernism of the post-war period – emanates from these strangers who take up the entire frame. We’re thrown into the centre of the physical and emotional movement of the urban body. Was it not Sid Grossman who said, ‘photography can make use of the convincing power of reality to create personal statements that express the strongest human feelings, even those of the photographer’? That was his way of exploring the human condition, of asking questions about the fate of the poor and of the elderly, about a conservative society that was becoming consumerist at a time when, in Europe and particularly in France, so-called humanist photography was about to emerge.

Levinstein was also convinced that emotions and states of mind are reflected in bodily postures. Which is why he placed great importance on choreographing bodies and postures. His photography is marked by radical framing techniques that cut through flesh, isolating certain gestures, sometimes even cutting off heads. There is no space here for old photographic realism, for Fine Art. Powerfully unprecedented and modern, his images, which reflect a revolutionary formal and expressive freedom, create an aesthetic divide. The formal influence of the avant-garde European cubists and constructivists is evident. Abstraction is waiting in the wings.

Moving, raw, sensitive, Leon Levinstein creates a physical, carnal relationship to his models through his graphic, untreated, striking snapshots. As a result, he was unconsciously a part of the prestigious tradition that art historians now call the New York School, which included Diane Arbus, Weegee, Saul Leiter, Lisette Model and others.