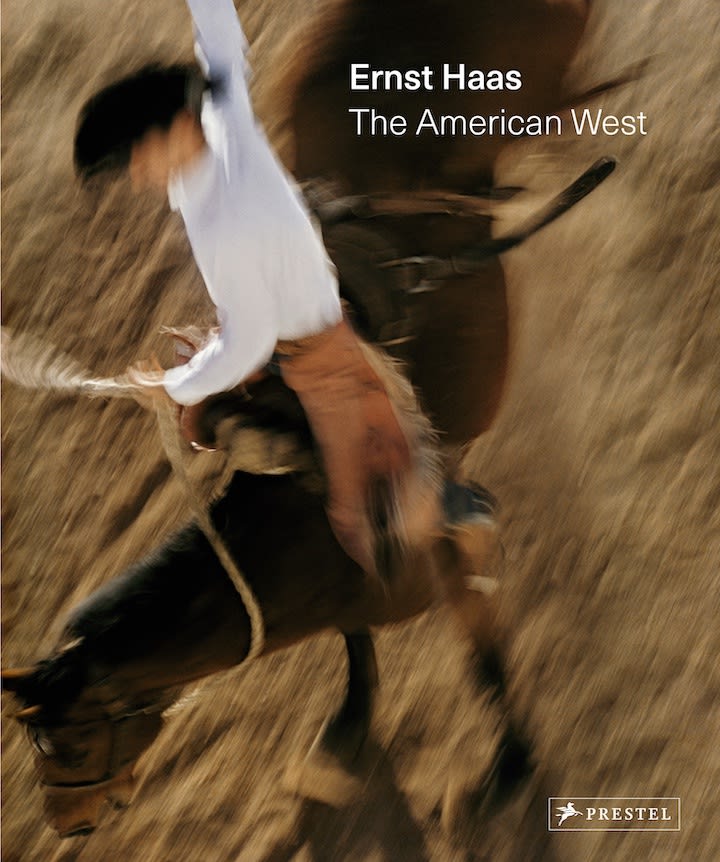

Ernst Haas: The American West

On the occasion of the publication of the book The American West, Les Douches la Galerie is pleased to present its fourth solo exhibition of Ernst Haas. Taken between 1952 and 1981, the thirty-two photographs presented here reflect his sensitive explorations of the Western landscapes and the broad technical palette that characterizes his work.

Opening on November 7th, 2022 from 6 to 9 pm

In the summer of 1952, the Austrian-born émigré photographer Ernst Haas embarked on a road trip into the heart of the American West. On assignment for Life, he hitchhiked along the barren desert roads of New Mexico in search of the mythical West that had fascinated him as a child. (...) The trip resulted in a six-page spread in the magazine entitled “Land of Enchantment: A Hitchhiker with a Camera Records New Mexico’s Many Moods,” which contained images that set the tone for his later, much more extensive coverage of the American West. The story included shots of wide expanses of sky, with a road lined with telegraph poles, receding far into the distance along an empty, dusty road, while in another image a Native American woman is tightly framed on the left of the composition, with a child and another woman carrying a baby, skillfully composed in a triangle that leads the eye toward the pueblo in the background. These themes formed the seed of an engagement with the myth and the reality of the American West that sustained Haas for the next thirty-four years. And according to Inge Biondi, the trip also led him to the other theme that defined the rest of his career: how to engage and understand the world through the medium of color, as she noted, “While photographing in black and white in the New Mexico desert, he experienced a great longing for color. Thus began a life-long odyssey of exploration of the uses and meaning of color in photography.”

Haas had arrived in the United States in 1950 at the invitation of Robert Capa, who had appointed him to be the US vice president of Magnum Photos, the prestigious and iconic photo agency that Haas had joined the year before. Joining Magnum was a decision he had made to try to maintain his independence from the editorial world, as in 1949 he had also turned down an offer from Life to become a staff photographer, writing in his letter of rejection that “there are two kinds of photographers—the ones who take pictures for a magazine to earn something, and the others who gain by taking pictures they are interested in.... What I want is to stay free, that I can carry out my ideas.... I don’t think there are many editors who could give me the assignments I give myself.” (...)

Haas clearly felt that his move to the United States opened up new creative opportunities as well as commercial ones, as he reflected, “Looking back, I think my change into color came quite psychologically. I will always remember the war years, including at least five bitter post-war years, as the black and white ones, or even better, the grey years. The grey times were over. As at the beginning of a new spring, I wanted to celebrate in color the new times, filled with new hope.” (...)

Haas truly did understand the idiosyncrasies of Kodachrome; as color slide film is very unforgiving, the exposure has to be perfect in camera as no postproduction can be done. From the very beginning Haas was a master of controlling this difficult medium as the rows and rows of perfectly exposed images in his archives at Getty Images attest to. (...) In his studies of rock faces with their infinite variations of a single color, he played with subtle gradations of tone and color, yet still retained a sense of depth and movement in the frame. (...)

As one of the pioneers of slide photography, Haas found that his ability to use color in a powerfully aesthetic as well as symbolic way was in high demand, and he used this to his advantage in securing commissions that allowed him to pursue his exploration of the nature of the United States. (...) He was astute at using this paid work to buy him the time to pursue his own vison, and often used the downtime during commercial work to shoot his own personal photographs, explaining, for example, how “during movie making, when locations are off the beaten track and long periods of waiting occur between takes, I have always used the opportunity to build up my collection of photographs of natural phenomena.” Indeed, Haas produced many of his most memorable photos while on movie sets, in particular during the filming of Little Big Man starring Dustin Hoffman, where the meticulous recreating of the lives of Native Americans allowed him to transport the viewer back into the nineteenth century. (...) Little Big Man offered Haas the opportunity to extend and deepen his connection with Native Americans, who he had been documenting for several years by this point, having photographed them extensively for a story published in Look magazine in 1970 entitled “America’s Indians, a Conquered People Wake Up.” (...) Haas clearly felt a strong connection with their philosophy and way of life, recalling, “In the country of the mesas and adobes I have slept under the stars with the Indians, seen the world from their point of view, talked philosophy in tepees, and felt a strong affinity.” But he was also acutely aware of how their culture and way of life been subverted and destroyed and then compromised by the white dominance of the West. (...)

Despite his reservations about the banality of advertising and its negative impact on the landscape, Haas was of course deeply connected to the commercial world, as his work on perhaps one of the most famous and successful campaigns ever attests to. Haas first began working on the Marlboro Man account in 1972 and continued regular campaigns for them up until his death in 1986. (...) Haas’s style of shooting was perfect for the ads, as he was able to capture the movement and energy of the riders against the epic backdrop of the plains and mountains of the West that he knew so well. (...)

Haas was also undoubtedly aware of his place in the photographic tradition of the American West, making a pilgrimage to Big Sur and Point Lobos in 1976 to acknowledge his debt to Edward Weston, about whom he confessed to be “greatly inspired by his work and would like to pay tribute to him,” and who had “taught me how to electrify a picture that does not move and make it move.” In his turn, Haas was a significant influence on a new generation of photographers who were exploring how to use color creatively to express meaning and not simply for its chromatic attraction. (...)

Haas thought of himself as a poet with a camera, and his extended exploration of the American West is a prime example of how he sought to transfer and translate his own knowledge, experience, and sensibility into his images by using the full range of visual strategies available to him, and even developing new and innovative ways to reflect the world through the lens of the camera. His extensive writings and interviews on the nature of the medium reveal him to be an image maker who thought deeply about the very nature of photographic communication. His philosophy in this explanation of how having a distinctive visual signature has to come from within the photographer is perhaps best summed up in the following: “Style has no formula, but it has a secret key. It is the extension of your personality. The summation of this indefinable net of your feeling, knowledge, and experience. Take color as a totality of relations within a frame. Don’t ever overanalyze your results! Don’t ever try to find your own secret of the one which you admire. One does not try to catch soap bubbles. One enjoys them in flight and is grateful for their fluid existence. The thinner they are, the more exuberant their color scheme. Color is joy. One does not think joy.”

Paul Lowe

Extracts from the introduction to Ernst Haas : The American West, Prestel, 2O22